Use the power of storytelling in tech to get promoted faster

Communication techniques that build your executive presence

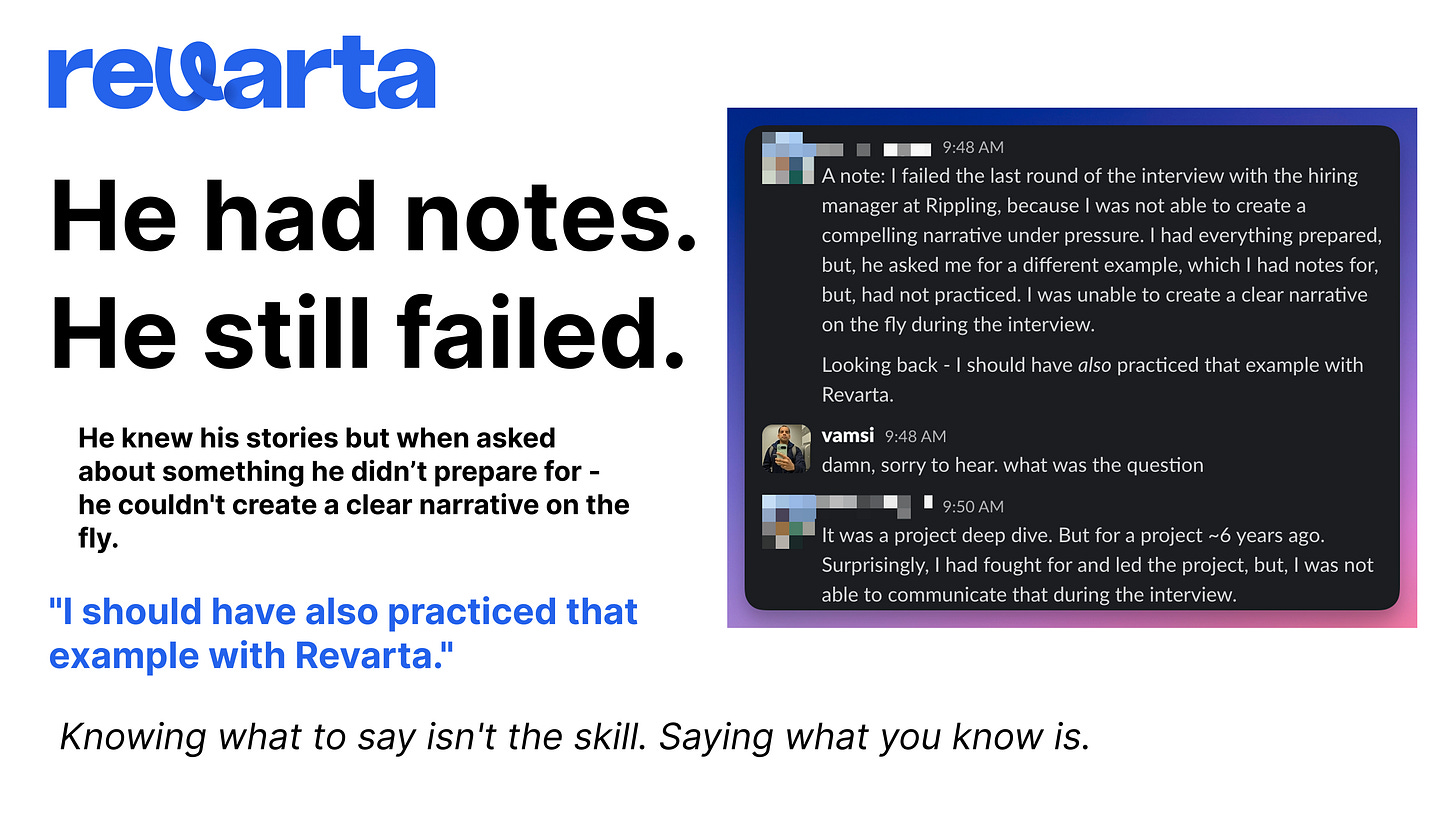

📣 “He Had Notes. He Still Failed.” (Sponsor)

You know your interview stories. But can you tell them clearly under pressure?

Most engineers prep by writing notes. But writing isn’t practice. Revarta gives you live audio interviews with follow-up questions and feedback on what’s actually landing.

Built by a hiring manager with 1,000+ interviews at Amazon an…